Issue 4.3 | July 2013

In this Article: doing business out of self-interest makes for bad business.

by Jonathan Wilson

Ten years after the wrack and ruin of genocide in Rwanda, I visited the tiny but infamous country. Standing by mass graves in which were stored the remains of hundreds of thousands murdered in just a few weeks in 1994, it was startling to consider how, just a decade out of the hell of inter-tribal hatreds and horrific violence, Rwanda was an emerging miracle of social healing and rapid economic growth (at 9%).

Together with corporations, churches and development organizations, the government intentionally pursued both social reconciliation and commercial development that addressed the real needs of Rwandans. Throughout the country I witnessed social entrepreneurship initiatives enabled primarily by micro-credit and community banking systems. These initiatives, and others like them elsewhere, preceded a wider shift now underway throughout the world of commerce: to do business to do good.

But if one of the founders of capitalism is right, this is all a little misguided: “I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good,” said Adam Smith in in his seminal work, The Wealth of Nations. The year was 1776, an auspicious one not just because it witnessed the publication of his foundational work on capitalism and free markets, but because the American colonies had just declared their intentions for their own bit of market freedom. The world fundamentally altered in those years, cementing the political and economic frameworks within which you and I operate today.

The Invisible Hand

To this day, the commercial world operates almost religiously by the permission seemingly granted in Smith’s claims (and later, Milton Friedman’s) that the business of business is simply to make money, and everything else be damned: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” Self-interest, Smith argued, is the driving force behind the creating of value that others utilize or consume. And where self-interest might descend into abuse or exploitation, the free market by its very nature introduces what Smith called an “invisible hand” of correction: competition. For the moment you gouge or underserve your customer, your competition (acting in self-interest) will quickly take the opportunity to improve upon your product or service and thus gain that customer from you. This competition forces everyone in a free market to think of the customer even as they think of lining their own pockets – all out of self-interest.

In very basic terms, this is true. This is indeed how the market usually works. But if Adam Smith’s claim is not only true, but how things ought to be, then we should be able to state his claim in positive terms: “I have known much good done by those who trade primarily for their own gain.” Put in that way, however, the claim clearly takes strain under the burden of much evidence to the contrary.

The Dividends of Self-Interest

To illustrate, let’s look briefly at the world of television. As you probably well know, the idea of the long tail* hasn’t made it to the TV industry: in other words, you don’t pay for what you get, you pay largely for what you don’t get. Americans typically pay around $70 a month for 200+ TV channels. They view about 14 of them.

This is a classic example of self-interest at work, as the value traded between provider and customer is in no way equitable. TV customers net out at a loss of value, as they are in no position to utilize the massive range of choice they (had to) purchase. According to Smith, the counterbalance to this cynical exploitation of the TV subscriber should come from the competition. In television, however, the competition simply colludes in perpetuating this unjust value-exchange. Instead of competing by undercutting their competitors (thinking of the customer), they compete on equivalent terms with whoever first thought up this horrible business model. These are the dividends of self-interest.

Another form of competition, however, lurks around the corner: or, more precisely, behind your screen. By introducing on-demand streaming video online, Netflix, YouTube and even the lacklustre Hulu are slowly gaining (still relatively tiny) market share in this space. They are held back by the difficulty of competing with the diversity and availability of cable TV programming but also by the move of TV companies to increase the online availability of their channels to their cable TV subscribers, at no additional cost.

The Invisible Hand is a Miserly Hand

The day may come when Adam Smith’s truism will play out and the disruptors of the TV industry will win the day for the customer (albeit, presumably, out of self-interest). That’s irrelevant to my point.

For what this whole sham really shows us is that while the Invisible Hand may eventually do its work, it really is a less than optimal way to create value for the customer. Self-interest, along with self-interest-driven competition, yields the meanest forms of value. In fact, along the way, a tremendous amount of available value is wasted. Adam Smith’s version of Capitalism is value-inefficient.

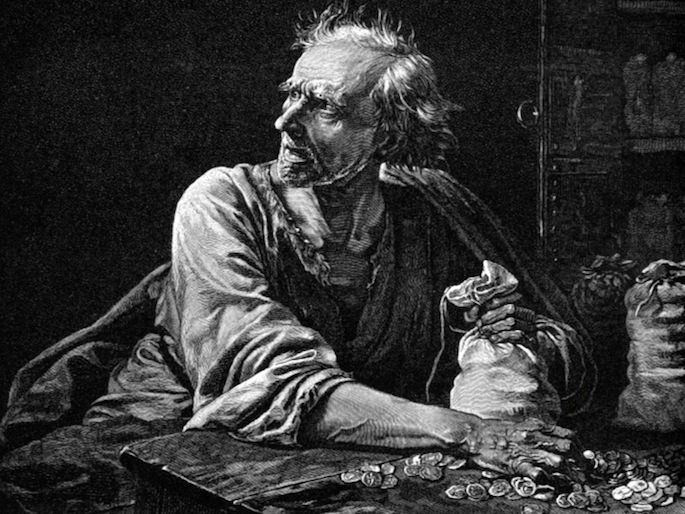

The one in business solely as a profiteer is, at heart, a miser, and will provide accordingly to his or her customer. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the company that pursues business that matters creates value that lasts. Commercial greatness is a form of leadership. Leadership happens when an individual or group sees what isn’t right or good or optimal, and does something about it that is robust and substantial.

So the most important question to ask of a company is not, “is it profitable?” but “is it a leader?” For to be a leader, it will create value in the marketplace and in the world that other’s can’t, and won’t. This value will matter. This value will last. Inevitably, the profit will follow.

Another soul insight from www.leadbysoul.com.

Leadership by Soul™, Trademark and © Soul Systems, All Rights Reserved.

*The Long Tail: in business model terms refers to the possibility of near-infinite customization.